A journey into the world of Italy's racist soccer thugs.

VERONA,

Italy -- Right up until he started quoting Hitler and dropping N-bombs,

my new friend was a great dude. I'll call him The Hooligan. A more

generous host would be hard to find. Soon after we met, he made sure we

stopped at the one place in town that served Campari correctly. He

speaks eight languages, and seemed nothing like the Hellas Verona fans

I'd read about, the neo-fascist, neo-Nazi, racist thugs. The Hooligan

insisted the Veronese just have a dark sense of humor and refuse to wear

the yoke of modern political correctness.

Now we are headed toward the terraces of the stadium. Soon I'll be packed in with the hard-core fans, three people for every seat, chest to back, eyes burning from smoke bombs. Near the entrance to the stands, I ask The Hooligan to translate any chants hurled down at the players. He is an old-school soccer thug, not on a first-name basis with impulse control. His eyes are slate blue, and his face has darkened with intensity as kickoff approaches. His voice is a sharp blade.

"How about, 'You're a f---ing n-----'?" he says, and we walk inside.

The ghost of Mussolini rides through the swampland he turned into farms, the sound of his bike's engine going tom-tom-tom in the dark. Some locals swear it's real. A famous Italian novelist, Antonio Pennacchi, saw the ghost when he was a child. Many still love Mussolini in Latina, one of the towns the dictator built south of Rome after draining the marshes. The old cab driver remembers not having to lock your door when Il Duce ran the country. The municipal building is still shaped like an M, in his honor, a reminder of a past that cannot be seen unless you fly high over the confusion below.

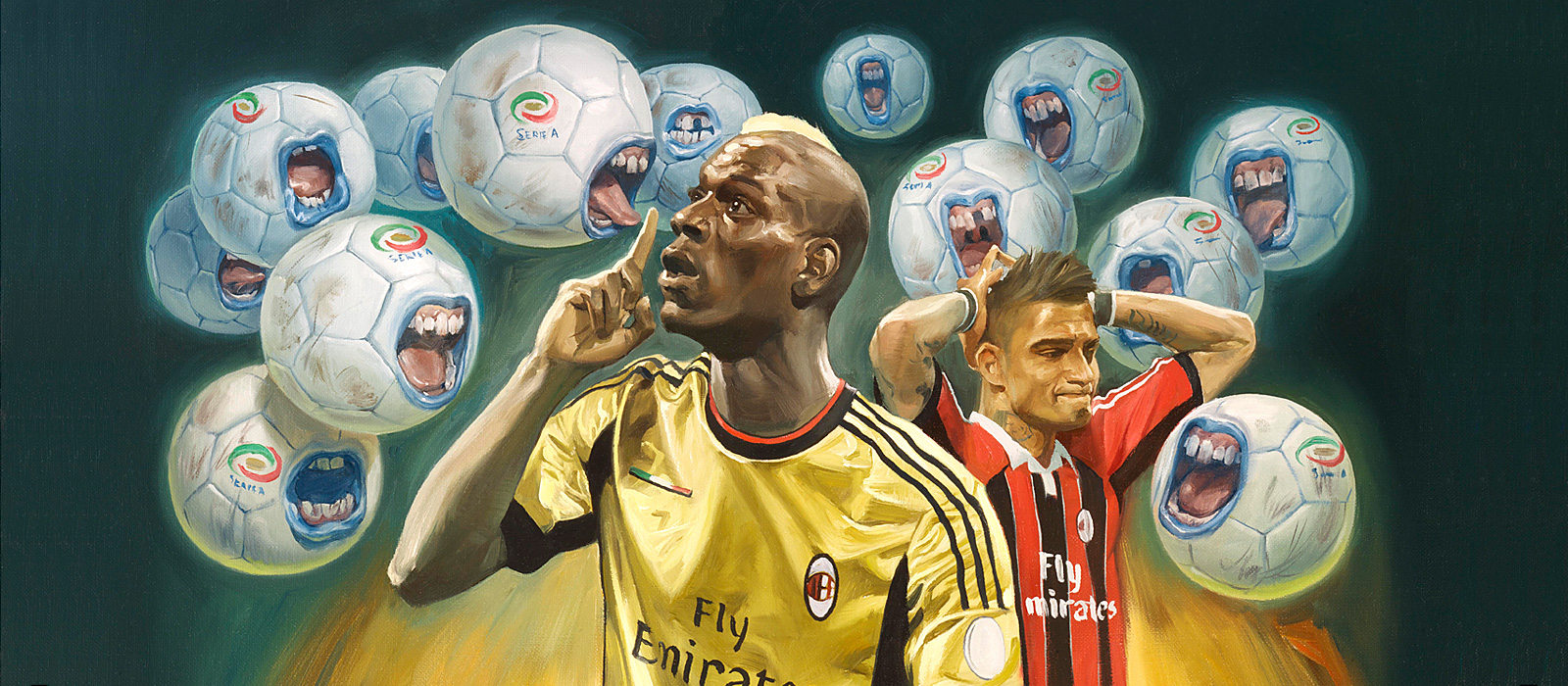

Pennacchi lectures me that American democracy is not morally superior. What Mussolini did in Africa, we did to the Indians. What Mussolini did to the Jews, we did to the African-Americans. He barks when I ask him to put the nostalgia for fascism in context with the epidemic of racist chants in soccer stadiums, especially the slurs against black AC Milan stars Kevin-Prince Boateng and Mario Balotelli.

"You are simplifying!" he says.

He stands up, imitating the way Balotelli appeals for a foul to the officials, moving around like he's been shot, the curse words flying in Italian.

"Balotelli is an asshole," he says. "No matter his color, he's an asshole."

The steam runs out.

"We are all assholes," he says. "Man is a beast."

Pennacchi goes outside and sinks into a plastic chair, lighting a Marlboro. He exhales a big cloud of smoke, inhaling back through his nose, quoting a philosopher I don't know.

"The Hitler inside every one of us," he says. "The good and the bad are mixed inside."

He ashes his cigarette.

"The road to civilization is very long," he says.

The rabbit hole opened when Boateng walked off the pitch during a match in Busto Arsizio. It was Jan. 3, in a small mountain town in the north of the country, a picture postcard of bell towers and winding streets. Serie A, the top division of Italian soccer, was in its mid-season break, so Milan had scheduled a friendly against a small local club, Pro Patria. When Boateng touched the ball for the first time, a small part of the crowd made monkey noises: Oo -- oo -- oo -- oo.

It was a little stadium, and Boateng could see their faces. Fifty or so people called him an animal. He locked eyes with them and could see the hate. He pointed to his head, to say, "You're an idiot." The chants went on for 20 minutes: Oo -- oo -- oo -- oo.

Boateng had been abused before and had ignored it. This time, he kicked the ball at the fans, took off his jersey and walked to the locker room. His teammates followed. Something important happened at this moment, which didn't get reported much in the frenzy that followed: Most of the stadium stood and applauded him. Only the small group of fans screamed and whistled. Some laughed.

The team boarded its bus and headed back to the AC Milan compound.

When they arrived, Boateng insisted they practice. He needed to run.

Tension still filled the air. The managers rolled out the balls, and

Robinho immediately kicked one off the pitch, turned to Boateng and

asked if they could be finished. Everyone laughed, and the jokes began,

about firing a ball into the stands whenever they were losing. The

players thought they'd made it through one bad day.

They were wrong.

Now we are headed toward the terraces of the stadium. Soon I'll be packed in with the hard-core fans, three people for every seat, chest to back, eyes burning from smoke bombs. Near the entrance to the stands, I ask The Hooligan to translate any chants hurled down at the players. He is an old-school soccer thug, not on a first-name basis with impulse control. His eyes are slate blue, and his face has darkened with intensity as kickoff approaches. His voice is a sharp blade.

"How about, 'You're a f---ing n-----'?" he says, and we walk inside.

Lost in the Pontine Marshes

This story is about a red motorcycle.The ghost of Mussolini rides through the swampland he turned into farms, the sound of his bike's engine going tom-tom-tom in the dark. Some locals swear it's real. A famous Italian novelist, Antonio Pennacchi, saw the ghost when he was a child. Many still love Mussolini in Latina, one of the towns the dictator built south of Rome after draining the marshes. The old cab driver remembers not having to lock your door when Il Duce ran the country. The municipal building is still shaped like an M, in his honor, a reminder of a past that cannot be seen unless you fly high over the confusion below.

Pennacchi lectures me that American democracy is not morally superior. What Mussolini did in Africa, we did to the Indians. What Mussolini did to the Jews, we did to the African-Americans. He barks when I ask him to put the nostalgia for fascism in context with the epidemic of racist chants in soccer stadiums, especially the slurs against black AC Milan stars Kevin-Prince Boateng and Mario Balotelli.

"You are simplifying!" he says.

He stands up, imitating the way Balotelli appeals for a foul to the officials, moving around like he's been shot, the curse words flying in Italian.

"Balotelli is an asshole," he says. "No matter his color, he's an asshole."

The steam runs out.

"We are all assholes," he says. "Man is a beast."

Pennacchi goes outside and sinks into a plastic chair, lighting a Marlboro. He exhales a big cloud of smoke, inhaling back through his nose, quoting a philosopher I don't know.

"The Hitler inside every one of us," he says. "The good and the bad are mixed inside."

He ashes his cigarette.

"The road to civilization is very long," he says.

Dispatch from the madness

I've given up hope of ever fully understanding the fractured things I saw while chasing the Serie A soccer circus around Italy. Let me be honest. I got sent to write about racism, which I found in staggering amounts. But Italy isn't like America, and racism there is tied into a thousand years of feuds, and hatred of anyone different, even if they're from only a few miles away, and fascism, and the recent wave of immigration. That's all in here, but it's unfair to hide my predicament, which became clear after only a day or two. I'd fallen into a parallel universe of contradictions.The rabbit hole opened when Boateng walked off the pitch during a match in Busto Arsizio. It was Jan. 3, in a small mountain town in the north of the country, a picture postcard of bell towers and winding streets. Serie A, the top division of Italian soccer, was in its mid-season break, so Milan had scheduled a friendly against a small local club, Pro Patria. When Boateng touched the ball for the first time, a small part of the crowd made monkey noises: Oo -- oo -- oo -- oo.

It was a little stadium, and Boateng could see their faces. Fifty or so people called him an animal. He locked eyes with them and could see the hate. He pointed to his head, to say, "You're an idiot." The chants went on for 20 minutes: Oo -- oo -- oo -- oo.

Boateng had been abused before and had ignored it. This time, he kicked the ball at the fans, took off his jersey and walked to the locker room. His teammates followed. Something important happened at this moment, which didn't get reported much in the frenzy that followed: Most of the stadium stood and applauded him. Only the small group of fans screamed and whistled. Some laughed.

ESPN The Magazine

They were wrong.

Heritage and hate

Riccardo Grittini, one of the men who yelled monkey chants at Boateng, stands with me in the town square of Corbetta. The search for understanding begins here, half an hour from downtown Milan, with a guy who looks like the second piccolo in a high school band. I don't know what I was expecting. Horns? He's 22 going on 16. Newspapers ran Grittini's photo back in January, but his head shot looks older than his face. I can't picture him looking at another human being and screaming: Oo -- oo -- oo -- oo. What could possibly have made that seem like a good idea?His hometown is like a thousand Italian villages. Narrow lanes gently bend toward the central square, which has a church, a trattoria, a place to drink espresso and buy cigarettes. Flowers grow on balconies. The church bell rings. It's like a movie set. Grittini is the local official in charge of sports; he thinks I've come to talk to him about an event he is organizing, visibly deflating when I bring up Pro Patria.

"You can do what you want with Boateng, but for me," he says, "it's a thing that I have erased."

The balding mayor, Antonio Balzarotti, comes over and welcomes me to town. "He was wrong, for sure," he says, "no doubt about it. We are not against Boateng and his campaign. Here, nobody is racist."

He offers proof. In the past, he says proudly, he rented two apartments he owns to blacks.

Everyone who passes Grittini smiles and waves. Birds chirp. Kids play in the square, and the fountain splashes water. Grittini loves this town, was born here and will be buried here. He's wearing rubber bracelets on his wrist. One carries a hand-written message: Prima Il Nord.

It's the slogan of his political party, the Lega Nord, a right-wing group founded on the desire to see the wealthy North of Italy split from the "economic dependency" of the South. The same complaints the Lega Nord once made against immigrants from southern Italy, they now make against immigrants from other countries: They bring crime and filth, take away jobs and, perhaps most important, bastardize Italian identity. A party leader advocated the Italian navy fire on boats of African immigrants. A party poster shows an American Indian with the slogan: "Immigration was forced upon them. Now they live in reservations!"

My Italian friends tell me that Lega Nord also runs a lot of small towns, and that not everyone who votes for them is nuts. Lots of reasonable people support parts of their platform, primarily the pro-business policies. I don't know where Grittini falls on the Lega Nord spectrum. I don't know what was in his heart that day in the stands, if he was angry, or drunk, or just got caught up in the mob. But I do know that, all around him, in his town and in his political circle, there lives a palpable fear that something very old and precious is, right at this moment, being ripped from their grasp. Yesterday is familiar. Everything else makes them afraid.

The Amazing Technicolor Football Club

They are afraid of the mohawks.I'm at AC Milan headquarters, standing on the lush terrace with vines and flowers hanging from pergolas. Down below, I see Balotelli, who is the same age as Grittini, walking up to lunch. He's by himself, checking his phone. From here, I can see his blond mohawk, though I can't make out the lines shaved on the sides beneath it.

The team's four star strikers -- Balotelli, M'Baye Niang, Robinho and Stephan El Shaarawy -- wears a mohawk. Balotelli keeps his dyed blond. Boateng does, too.

The team photo on the wall looks like a Benetton ad.

There's a Muslim Italian, El Shaarawy, born to an Italian mother and an Egyptian father.

There's a German with Ghanaian roots, and Frenchman with Senegalese roots.

There's a black Italian, Balotelli, the embodiment of a still-unformed future just as surely as Corbetta embodies the past.

The Balotelli affair

Balotelli's life is a Fellini movie, with cameras flashing wherever he goes, and news of his weird adventures dominating the tabloids. In a day or two, he'll drive his white Ferrari onto a go-kart track. He loves go-karts, but his contract forbids him from riding in them. So, instead, he'll take his $300,000 Ferrari out for a spin.Milan signed him from Manchester City just 26 days after Boateng took off his jersey and left the field. Before Balotelli's first game, Paolo Berlusconi, a team official and brother of former prime minister and AC Milan owner Silvio Berlusconi, was caught on videotape saying, "OK, we are all off to see the family's little black boy."

Balotelli's mere presence in Italy has caused a long festering sore to rupture, bringing hidden rot into the light. A nation has projected its hopes, and its fears, on him, a strain that shows on his face. He's been distancing himself from old friends, cutting off anyone who talks about him to reporters, even if they say nice things. He's angry a lot of the time, which is probably not how he imagined his homecoming. Mostly, he seems like a young man desperate to belong; he even got the British royal crown tattooed on his chest after playing there, holding tight to the part of him that felt English.

He was born in Italy. He grew up two hours from Milan in a little town named Concesio, taken in by a white Italian couple when he was 3 years old. Balotelli's birth parents are immigrants from Ghana, and although he looks like them, he sounds like his provincial neighbors, speaking with the well-known Brescian accent, a low rumbling growl. The region of Brescia famously doesn't like outsiders and votes for the Lega Nord. An old underground cartoon sums up the local attitude. It shows a deep trench at the edge of Northern Italy, with a clear message: Let's get rid of the Africans.

'You're gonna get a banana'

Kevin-Prince Boateng comes into the posh drawing room in the AC Milan headquarters rapping Snoop Dogg. The word "believe" is tattooed on his left hand. Wealthy, engaged to a swimsuit model, he's left behind a childhood in the Berlin slums. The 9-year-old him would be awestruck by the room in his house completely filled with sneakers, which he cleans carefully with toothpaste. But the 9-year-old him also has scars, ripped open that afternoon on the Pro Patria pitch, when strangers looked him in the eye and called him a monkey."It's happened to me before," he says.

He wasn't Boateng then, just a kid named Kevin with a German mother and a Ghanaian father. During an away game, the father of an opponent said, "Little n-----, for every goal you score, you're gonna get a banana."

Boateng repeats those words sitting in the quiet, peaceful lounge. "It's inside of me," he says. "I will never forget the father. He had a big beard and no hair. I even remember his son. I remember the face of his son. I wanted to kick his son so hard. I didn't. I scored a goal, and we won the game. This I remember."

Boateng believed if he got rich enough, if he won enough games, scored enough goals, he could outrun the bald man with the big beard. For years, he did. During his first three seasons at AC Milan, he never was abused.

Then he rode a bus to Pro Patria. That day was just the beginning.

A crowd at a match with Florence's team, Fiorentina, abused Balotelli. At Juventus, Boateng looked up in the stands and saw two men wearing the team's famous black-and-white jerseys making the monkey chant: Oo -- oo -- oo -- oo. Boateng yelled at them in the stands, "Come down! Do it in front of me!"

Since then, he's been speaking out against racism, meeting with the head of FIFA, making a speech at the United Nations. He'd been known as a party boy, getting caught once in a nightclub the night before a game. That one day of monkey chants gave him focus, a way to honor a nine-year-old boy's fears, just as a room of sneakers honors that boy's hopes and dreams.

He's troubled by the racist chants coming from the terraces, which aren't new to Italy but are to him. Every week or two, it seems there's another news story about a crowd chanting vile things at soccer players, about clubs being fined or forced to play in empty stadiums. Boateng can't figure out the reason so many seem directed at AC Milan. Why them? Why now?

"It never happened," he says. "Now it's crazy. It happens every game."

Neighbors are for hating

My train rattles through the Tuscan countryside traveled by Caesar and Charlemagne, creaking and swaying. I'm headed back in time, looking for an answer to Boateng's question. The genesis of almost everything that is happening in present day Italy can be found in the past. Tonight, Fiorentina is playing at Siena, a town surrounded by ancient city walls, with narrow turning lanes and steep alleys, all converging on the Piazza del Campo. The two cities have been rivals for a thousand years, a reminder that every city in Italy is much older than the nation.My friend Fred Marconi picks me up at the station. A Siena native, he's wearing a Ramones T-shirt. Elvis glasses rest on the dashboard. We're going to the game. Siena needs to win at least two, and maybe all, of its final three games to avoid relegation.

"Siena is going through a terrible struggle," he says.

The oldest bank in the world is in Siena, Monte dei Paschi, and for centuries it operated with caution, holding great wealth, becoming a benefactor for the town, even sponsoring the beloved soccer team, which wears the bank's name on its jerseys. The bank invented the concept of credit, and the word bankruptcy, sending these ideas out into the world, where they began slowly working their way back. The circle took 541 years.

The managers got greedy, expanding, taking on debt. Then the financial crisis hit in 2008, and after four years of hiding huge losses, the bank almost defaulted. Monte dei Paschi is now supported by the government. All told, the bank lost close to a billion dollars. An official jumped out his window into the piazza below, killing himself. The bank is dropping its sponsorship of the team, which is close to being relegated.

"I don't even know, honestly, if the franchise will still exist next year," Marconi says, "or if Siena will go bankrupt. It will be a disaster, a major disaster."

He drives past the exit for the stadium. Rows of trees line the road, pine and cypress. Castles rise from the hilltops. There's a place he wants to show me first.

"Our Little Big Horn," he says, shifting into the next gear and tearing off through the winding Tuscan hillside roads, driving like a maniac. An old battlefield will help me understand the Florence-Siena rivalry, and to see how deep the roots of identity run in a land much older than the modern nation drawn on its surface. Marconi's family has lived in Siena for at least 500 years -- the paper trail ran out before relatives did -- and he explains that the town is proud of its bitter and eternal feuds. Even today, the town is divided into neighborhoods, or contradas. Twice a year, the contradas compete in Il Palio, the oldest horse race in the world. Each neighborhood is named for an animal or a powerful force in nature, and children are baptized into the contrada just as they are baptized into the church.

"My son is a Porcupine, like I am," he says. "If there would be any sign of love or affection to a lady from the She-wolf, Lupa, our enemy, I would not interfere. But, honestly, I will have serious issues. I'll say that. I hope it never happens."

This isn't some old man talking. He is a 42-year-old graffiti artist who makes wine and plays bass in a rock band. He's got a Ramones tattoo. He baptized his 3-year-old son on the 750th anniversary of the battle that took place on the peaceful field he is driving me to see.

Changing lanes, he swerves in and out of game-day traffic, telling the story.

"This was one of the biggest battles in the Middle Ages," he says. "It was Sept. 4th, 1260. Dante talked about this battle in 'The Divine Comedy' and said that was a terrible day. The Sienese turned the Arbia River into a red river of blood. We actually exterminated the Florentine army."

After the battle, the city-state of Siena flourished. Work started on a cathedral, which would be the biggest in the world. Some businessmen founded a bank. The reign lasted almost 300 years, then the Florentine army got its revenge, taking the town.

The cathedral remains unfinished.

Marconi barrels toward the battlefield crowned with cypress trees, and, just as he is crowing about the ancient victory, a car passes and he notices a flash of purple. Fiorentina colors.

They're from Florence!

My easygoing friend transforms, just for a moment, into a warrior, filled with hate. He leans on the horn, flipping them the bird.

"F--- you all!" he screams.

After the battlefield, we settle into the stadium. Fiorentina scores a quick goal, Siena never challenges, and, as the game ends, Marconi wheels around in his chair and bangs his head and fists against the wall. He climbs the hill toward the Campo. There's one home game left, in 11 days, against Milan.

"AC Milan is gonna be the team of the future," he says. "The game with AC Milan is gonna be sad. It's gonna be the end of something. It could be the end of everything."

A breeze blows, and he tries not to think about his team going bankrupt and ceasing to exist. Crossing a piazza, headed toward an unfinished cathedral, his phone rings. It's his wife. Their 3-year-old got a haircut today, and he had a specific request for the barber.

"My son has a mohawk," Marconi says proudly.

The new Italy

Everyone has talked to me about immigrants, but I haven't seen many of them. Where is this dangerous flood that so threatens the very foundations of Italian identity? Well, many live in transient villages, as far away from the sturdy stone walls of Siena as a human being can get, working as migrant field hands around Naples. I travel south. A local doctor, Renato Natale, drives me into a world where outsiders rarely go. He parks his car behind a church-run shelter, the home of last resort for people who've come to plant and pick tomatoes. "It's very difficult to understand the new Italy, even for us, who are Italians," Natale says. "There are more black people here than in Alabama."Two children run through the halls of the shelter.

The smaller boy is the child of a prostitute. He was born in Italy and isn't a citizen, since the law demands children have an Italian parent to be Italian. His hair is cut into a mohawk, and he's got lines shaved beneath it. I recognize it and tell him so.

"Balo-telli! Balo-telli! Balo-telli!" he yells in a sing-song voice, the voice growing softer until it disappears, as he runs outside to play with his older brother. I follow him, meeting a young man on the porch whose biceps strain the fabric of his shirt. Eric Andrews is an athlete, and he speaks English, which surprises me after a week of translators. Kids here get mohawks, he explains.

"The haircut is because they love Balotelli," he says. "That's why they do it."

About eight years ago, Andrews came to Italy to play soccer. He brought big dreams with him, and a nomad's past -- born in Sierra Leone, he moved to Ghana, then wandered around Europe, trying to find a home.

"Me," he says, "I've been moving around."

Back in Africa, he says, he played in the same club as current AC Milan star Sulley Muntari. They followed the same star in the sky, and now Muntari is married to the former Miss Ghana, living out "Gatsby," and Andrews is at this camp, living out "The Grapes of Wrath." "He has better luck," Andrews says, "but you can see where he is, and here am I."

He looks around.

A little fire smokes and smolders. Mattresses rest under trees with shapes on them. People sleep on the porch, and in chairs, wherever they can find a place that is either flat or soft. It's too much to hope for both. Most work the highway outside as prostitutes, or stand on the same blacktop and hope a farmer picks them up to earn a few euros a day in the fields. On the chapel walls, murals show Jesus helping workers in the fields and ministering to hookers on the road. The priest tried to paint Jesus black, but the African residents protested. "White is better," they told him. Someone puts cardboard on the fire, which pops and flames. There's a little girl, maybe 6 or 7, standing by the front door. Andrews tells me her mom is from Nigeria. She was born here.

"I am not Italian," the girl says in her small voice.

Someone built a reed hut. A group from Mali recently arrived, trying to escape the war. The whole thing looks exactly like an African village. This small piece of Italy is their entire world.

"They don't go into the white part of town," the director tells me.

The abuse begins when they cross that invisible line. Andrews has tried to understand his Italian neighbors, to dig down through the layers until he knows why the people who love tomatoes hate the people who pick them.

"Italians don't travel," he says. "That's how I see it. This is it. Someone who was born here, even in this small village, he has never even gone to Napoli before. That is how they are. Sometimes they even ask me, how did I come to Italy? I tell them I walked."

He laughs, a deep booming laugh still untouched by the hardness and despair around him. Andrews doesn't sweat in the fields. When he's not working at the shelter, he plays soccer for the local team. They are in Serie D, four rungs below AC Milan. They ride public buses to games, and he hears the abuse on the rides, and at the stadiums when he takes the pitch.

"Somebody will call me a monkey in front of the referee," he says. "I turn to the referee and say, 'Did you hear what he said?' The referee says I should keep quiet. That is what the referee tells me. Are you kidding me?"

He's 28 now. People tell him he might still make it, but he knows the truth. His window is closed; he's too old to change his life with the game that brought him here. Now he plays because he loves the way he feels with a ball at his feet, eyes up, looking ahead. He tries to ignore the monkey chants, and the slurs, even as he notices the abuse is getting worse.

"Boateng has not seen anything," Andrews says. "He needs to come here. I've been experiencing many things."

A black Italian, in full

Balotelli understands the kids in the refugee camp. When he was their age, what he wanted most of all was to fit in, to be like the people around him. A biographer, Mauro Valeri, told me that young Balotelli washed his hands in hot water to try to get the black off his skin. He also said Balotelli asked an elementary school teacher if his heart was black inside his chest. I don't know if these stories are true; I'm somewhat suspicious, since they read like something a white liberal Italian would want to be true.A well-known Italian journalist told me to "triple check" those details because they did not sound like the Mario he knows. Balotelli has hidden his vulnerable younger self behind a peroxide blond mohawk and armor made of bravado. Well, almost hidden. Buried in a tabloid tell-all from an ex-girlfriend was a detail that rings too true to be made up. As a gift, he gave her a box, and on it he had written, "Please never hurt me," with a sad face drawn on it.

Like Eric Andrews, Balotelli liked how he felt with a ball at his feet. Across the street from the apartment building where he lived, in between the supermarket and the church, was a pitch. This was his real home. When he stepped in between the lines, he found a place where being different wasn't bad. All he had to do was go down a flight of stairs, go out the gate, cross the road, and navigate a patch of tall weeds between the street and the stadium. He seemed safe there, creating an Italy where he belonged. Maybe that's why he's said he'll never be forced from a pitch by racist chants. He'd be letting the hatred drive him from his home.

It wasn't officially his home, of course. He wasn't a citizen, kept from representing Italy at the Beijing Olympics in 2008 because his 18th birthday was four days after the opening ceremony. Ghana tried to get him to play for its team, but he refused.

He was Italian.

In Italy, some opposing fans chanted: "There are no black Italians."

When he turned 18, Balotelli applied for citizenship, which he received in the city hall of Concesio, standing next to the family that took him in 15 years before. He posed for a picture with his mother and father, who both smiled, holding on to each other's arms. Balotelli smiled, too, not a cover-boy shot but the modest smile of a son with his family. Balotelli made himself a T-shirt after that day: Not only am I perfect … I'm Italian, too.

A month later, he debuted for the Italian U-21 national team. Only four blacks have ever played for Italy, and Balotelli was the third. The first, Fabio Liverani, was only 12 years ago. People accepted him. His father was Italian. I visited Liverani in Rome, and he took me into a storage room off a hallway, where he keeps his jersey framed from that first game. Next to it, there are photographs, one taken during the national anthem. His eyes are red. He'd looked in the stands and found his mother, who moved to Italy from Somalia to begin a new life. She was crying, and then he cried, too. When he first got the news that he'd represent his country, he'd called his mom.

"Our dream came true," he told her.

Every time Liverani hears the national anthem, he remembers that day. He'd never felt so Italian. During the 2012 European Championships, Valeri said his research showed some Italians saw Balotelli singing the national anthem before the game and turned the game off, disgusted. Something about him is different. Even though he's not the first black player on the national team, he broke a much less known yet more significant barrier.

He was the first black soccer player to represent Italy who didn't have any Italian blood.

The immigration fight

Balotelli was 2 years old when the Italian parliament passed "Act No. 91 of 5 February 1992." These were the last days of the old government, which disintegrated during the scandal known as Bribesville. At one point, half the members of Parliament were under indictment, and the dominant political parties collapsed. Italy rebooted. The man who exploited the vacuum was Berlusconi, who took office two years later, ushering the era of the tabloid sex scandal. There's something approaching performance art about the underage escorts in combination with a dying economy: While Berlusconi was screwing the youth, he was also literally screwing the youth.The first article of Act No. 91 denies Italian citizenship to anyone born in Italy without an Italian citizen parent; when the child turns 18 and passes a list of requirements, he or she may apply for citizenship. The reason I know about this law is because a national shouting match has erupted over it. The week I arrived, a new government took over in Italy, and one of the new ministers was an African immigrant, a doctor named Cecile Kyenge. She is Italy's first black minister, which is like being a Cabinet secretary.

Balotelli, who gives almost no interviews, offered public support, calling her appointment "another great step forward for an Italian society that is more civil, responsible and understanding of the need for better, definitive integration."

The Lega Nord opposed her agenda, a party leader asking her to come to Northern Italy "to see first-hand how mass immigration has turned Italians into a minority in the very neighborhoods in which they grew up." The extremists came out, too. A Lega Nord representative to the European Union parliament, Mario Borghezio, insisted that Kyenge would "impose tribal tradition" on all Italians. Borghezio, who is considered far outside even the right-wing mainstream, said Kyenge sounded like "a good housewife, not a government minister," then, he lashed out at Balotelli's qualifications to have an opinion on the immigration debate. "Balotelli agrees with her?" he said. "But he's not a minister, he kicks a ball around. To do that, you can be a Congolese or an African."

On Kyenge's first day in office, she announced that she would fight to repeal Act No. 91.

The blame game

A pickax changes my trip.I've been in Italy a week or so, and each conversation has moved me a small step closer to getting the place, then the whole damn country catches on fire. All it takes is a spark. Leaving the migrant worker shelter, where I'd met Eric Andrews, I check my phone. That's where I first read the breaking news alert. An immigrant from Ghana had gone on a rampage through the streets of Milan.

His name was Mada Kabobo. His record included past criminal offenses, and when his appeals process had finished, he would have been sent back to Ghana. That morning, he walked around at dawn, carrying a pickax on his shoulder. A voice in his head told him to swing it, and, in front of a local ice cream parlor, he did, burying the point in the head of an unemployed man going to get coffee, striking him four times all together. The man died on the street surrounded by pools of blood. Kabobo kept swinging, with people diving through open doors, trying to duck the heavy arc of the blade. Two others died in the hospital in the days that followed, and when the police interrogated Kabobo, all he said, over and over, was, "I am hungry."

The head of Milan's Lega Nord, Matteo Salvini, responded quickly. He didn't solely blame the killer; he also pointed responsibility to Minister Kyenge, whose attempt to grant citizenship to immigrants, he claimed, led to the attack. He announced the party would be gathering signatures to toughen the immigration laws that Kyenge is fighting against.

The intersection of football and politics

So what does the murder, and the reaction to it, have to do with soccer?The answer is in an obscure but important book about the Italian ultras, "Football, Fascism and Fandom," reported by a researcher named Alberto Testa. It came out three years ago, the only book to have gotten inside the walls of two of the most violent ultras groups in Italy, the Roma Boys and the Lazio Irriducibili.

Testa and his co-author discovered something obvious to anyone who's been in the terraces of Italy but shocking to me: In several places, the ordinary ultras -- organized groups of hardcore fans, to wildly oversimplify -- have been replaced by what Testa called "UltraS," who define themselves not just by the team they follow but by a neo-fascist political ideology. Roma and Lazio ultras hate the government more than each other.

This message resonates with part of the 38 percent of young people who are unemployed, a number that continues to rise. In America, most intellectual, angry youth go toward the left. In Italy, there's a trend to the left, to be sure, but there's also a sizeable group of alienated youth who go toward the far right. That's been true for several generations, but Testa discovered this generation's neo-fascist activists weren't just marching in the streets. They were also shouting in the stadiums.

The football terraces are their political megaphones.

What happened next was inevitable, really. Anyone in Italy since the murders knew what was building and on whom it would be released. AC Milan had a game 36 hours later, in Milan. A group of Roma ultras took their place in the visitor's section and waited for Balotelli to get the ball.

They were ready when he did, with a chant that managed to combine a nursery rhyme of vowels and virulent racism. They seemed pleased.

A … E … I … O … oo -- oo -- oo -- oo.

The referee warned the crowd, then stopped the game, the players gathering near the center of the field. The stadium made an announcement that the game would be abandoned if further racist chants were shouted. Balotelli looked as if he might snap.

Two minutes later, the game resumed.

Milan needed a win to secure a place in the Champions League, but the team seemed off, distracted. The game ended in a draw, and now Milan would have to beat Siena in its final game of the season or see Fiorentina slip past it in the standings. The next day, every paper in Italy ran huge photographs of Balotelli confronting the racists, staring down the ultras, with his finger to his lips.

The intersection of politics and hate

The Roma ultras, and their crosstown rivals from Lazio, are a mix of a violent street gang and the Cameron Crazies, sometimes making clever banners, or inventing funny chants, and other times sinking to the basements of human behavior.Italy's first football death came in 1979 during the Roma-Lazio derby, a Lazio fan accidentally killed by a Roma fan who thought a naval distress rocket was a regular flare. In recent years, two matches were stopped or canceled due to fan violence. Lazio ultras often display swastikas and fascist symbols, and the banners lean toward Nazi. In the late '90s, the Lazio fans unfolded a 160-foot banner aimed at Roma fans: "Auschwitz is your town, the ovens are your houses." They've held banners that managed to insult both the team's players and fans: "Squad of blacks, terrace of Jews."

The politics of the terraces often lack logic, praising ethnic cleansers and paramilitary murderers, the Palestinians, the Irish and the Iraqis -- anyone they see as oppressed by a larger power. The specifics of the battles don't matter as much as the ethos. Both the right and the left in Italy, for instance, revere Irish patriot Bobby Sands.

The everyday fans of Lazio and Roma come from all political and economic backgrounds, the roots of their fandom often going back to whichever team their grandfather supported. Many restaurants in Rome display a banner or sign from one of the two teams near the cash register, so customers know whether to strike up a soccer conversation. It is a town divided, which makes an attack on English fans this past November so surprising -- and terrifying, since it suggests new and shifting alliances.

Tottenham had come to Rome to play Lazio in the Europa League. The English team is based in a formerly Jewish neighborhood in London, which makes its fans frequent targets of racist chants around the world. The night before the game, a group of Tottenham supporters gathered in The Drunken Ship pub in a corner of the Campo de' Fiori, a small piazza with butcher shops, flower stalls and bars.

Then, with no warning, the windows shattered. Fifty or more men wearing helmets invaded the bar. Smoke bombs filled the air with the smell of used shotgun shells. They barricaded the doors. Witnesses said they chanted anti-Semitic slurs at the fans, who huddled under an assault of knives and clubs. Some English fans tried to escape, running down a narrow alley off the square, where they were trapped and stabbed. One man almost died. Everyone suspected Lazio fans. A week later, the police arrested two men in connection with the assault.

They supported Roma.

Pushed away from home

The racist chants finally get to Balotelli.He gives a rare interview to CNN, and his comments lead every sports page in Italy. The next time a soccer stadium echoes with monkey calls, he will take off his jersey and leave the field. All those years ago, at the pitch across from his house, he felt like he belonged. Now every monkey chant is pushing him away.

Boateng walked off in an exhibition game. This is different. Milan needs a win to secure a place in the Champions League, and its star player has drawn a line in the sand. The game is in two days, and Italy focuses on a single question: Will he or won't he?

Two other things happen at the same time. I don't know what they mean, but I know lines are intersecting.

Balotelli starts a Twitter feed, posting pictures and sending out messages, giving himself a public voice at last, to defend himself, to connect with people who support him.

He shaves off his mohawk.

'This is a revolution'

At a café just off the piazza where the English fans were stabbed, a man tells me a joke that goes something like this: A contest searched for the best memory in Italy. Three finalists remained. The first said he knew every train schedule in the country, then proved it by rattling off the stops and times. The second said he memorized all the phone numbers, quoting the dozens of Roberto Mancinis in Napoli. All very impressive, the judges said. Then the third contestant blew away the competition, winning the prize."I remember I was a fascist," he said.

James Walston sits in his chair and laughs. He teaches Italian politics and history, and he has agreed to help me understand why the football terraces have become incubators of hatred. He lives a few doors down, and he's seen the creeping return of a political ideology once thought dead. A German friend stayed with him not long ago, and she went cold one night, hearing drunken Italians wandering down the narrow alley singing old Nazi war songs.

He tells me the history. In the years between the end of the war and the fall of communism, some fascists remained. The one political party with fascist leanings consistently got four to six percent of the vote, with old Mussolini followers holding secret meetings. You could buy Mussolini calendars, and posters, but they were sold under the counter, in paper bags.

"Almost like buying pornography," he says.

Something changed. The first time he noticed was around 1991, around the same time neo-fascist politics entered the football stadiums. At the piazza near Mussolini's famous balcony, he saw 50 or so skinheads in boots, marching, giving the fascist salute and chanting, "Duce! Duce!" It was the first time he'd ever seen this in public, and he took comfort that it was just a small group of loonies.

Then Bribesville collapsed the government.

The new prime minister Berlusconi invited the National Alliance, a conservative post-fascist party, and the Lega Nord into his government. He brought politicians with neo-fascist leanings and connections into the mainstream, and, in a populist search for votes, he separated the good parts of Mussolini's empire from the bad. Alessandra Mussolini, Il Duce's granddaughter, got herself elected an Italian senator, and later threw her support behind the prime minister. My friend Terry thinks her holding public office might just be the single strangest fact in a country gone mad. "Can you imagine in Germany," he says, "someone with the name Hitler being in parliament?"

In actions and words, the Berlusconi government rehabilitated fascists, bringing them back into Italian life. Mussolini memorabilia is sold in the open, no longer hidden beneath the counter. Three months ago, Berlusconi said that Mussolini wasn't so awful, that his racial laws were a mistake but his reign had been good for Italy.

"Italy has changed in the last decade," Walston says. "This is not an existential crisis. It's a revolution. Italy goes through a revolution every generation."

Where does tradition end?

I step into the middle of the revolution, leaving Rome and taking the train north to meet The Hooligan. Enough intellectual discussions. I wanted to see what racist chants sounded like, and felt like, from a few inches away. A writer connected me with The Hooligan, and before I arrived in Verona, before we walked into the stadium together, he had asked just one question of me by e-mail: Are you white?Hellas Verona is playing its final game of the season, needing a win or a draw to return to Serie A after 11 long years relegated. My new friend, The Hooligan, gives an impromptu speech before the game. "This is a medieval town," he told me. "I am medieval. I am Veronese. We've been here 900 years. We have our colors. We have our traditions. It's the last corner of what is left. Everything is globalized. We are totally anachronistic. We are the only ones who still keep the flag flying. We believe in certain things."

I liked him then.

I liked his friends, and we rolled from bar to bar, ordering nice bottles of champagne. We talked about grapes, and how they feel guilty about being middle class when their parents lived as peasant farmers. A bottle of rosé appeared on the table. I was laughing, telling them how I expected that we'd be taking two-by-fours out in the streets, beating the crap out of cops, not discussing the bouquet of wine.

"We're extremely refined c--ts," someone at the table said.

Among the thugs

Kickoff is five minutes away.A man sits on the railing leading the cheers, and everyone listens to him. He's the boss. A hot fire burns by my shins, a bright red flare, and a guy takes smoke grenades from an olive drab jacket pocket and sets them off. The section looks like a Vietnam movie, the wind sending the blue smoke in swirls.

"That is the smell of the Verona terraces," The Hooligan says, breathing in the cordite.

There's someone pressed against my back, and I'm slammed into the guy in front of me, who has an enormous crucified angel tattooed on his back and the team logo inked behind his ear. Someone ashes a cigarette on my head and wipes it off. Then it happens.

Everyone around starts making monkey noises: Oo -- oo -- oo -- oo.

"Is there a black player?" I ask, peering through the smoke.

"It doesn't matter," The Hooligan says.

"You f---ing Southerner!" someone screams.

They rhyme "fantastica" with "swastika" and the people around me make the Nazi symbol with their hands. They sing a fascist song from the '30s and make the Roman salute, known to most as the Nazi salute. Then a chant starts. Time peels back. I look into the faces around me. Some are silent. Some are filled with rage as they scream:

"Sieg Heil!"

'Adolf Hitler. Perfect.'

I watch the second half a section over. It feels like a different world. Families sit together, sons and daughters, wearing blue and yellow, the team's colors. People drink tall boys, and shots they've sneaked in, but most are well-behaved. A lot watch sitting down. In fact, most of the crowd around me is sitting, like in a modern American stadium, and then I turn and look over my shoulder at the place I just left. When standing in the middle of the chants, it felt like everyone in the stadium was singing fascist songs, but really, it's just a small pocket of madmen.The Hooligan joins me, telling me his favorite chant, which, as a friend darkly will note later, manages the trick of both denying the Holocaust and taking credit for it: "The gas chambers didn't exist, but if they did, they were painted blue and yellow."

I just, I mean, I don't know what to say. I finally ask if that's what the people are screaming right now. A fan next to us looks horrified, shaking his head, saying, "Nonononono."

Verona gets the draw it needs, and the crowd rushes the pitch. The Hooligan stands next to me, looking down, then some fans start mocking the small section of visiting fans from Empoli, flipping them the bird. Groups of Verona fans tear down the goals and run around the track waving flags. The Hooligan loses his mind. He's screaming down at the fans to leave the field, to stop embarrassing the city, to stop desecrating their own goals. This seems like sort of a minor thing to me. Not to him, and a whole lot of other people around him. How a fan handles victory says more about Verona than the fact that a group of mercenary athletes won a game against other mercenary athletes. Swastikas are cool, but the ultras think pitch invasion is bush league.

They start the monkey chant at their own fans now.

Oo -- oo -- oo -- oo -- oo.

The Hooligan can hardly speak in the portal leading up to the seats. He takes a few steps, then curses, and turns to leave. Outside, cars honk, and fans hang out the windows, chanting "Serie A," and he wonders where all these people were when he and 120 friends traveled to the south of Italy when the team played in Serie C, just five years ago. He snaps his hoodie over his head, and his eyes burn. Rain starts to fall, and we duck into a bar. They bring us beer in short glasses.

"There is an ethic!" he growls. "A code of hooliganism."

Many years ago, Verona needed a win to avoid relegation, which it got, and some fans went on the field and got jerseys from the players. The ultras felt the players didn't deserve such adulation after a disappointing season, so The Hooligan and his brother went down to the pitch, slapped some, punched a few others, and demanded the fans march back into the locker room and give the jerseys back. They beat the crap out of anyone who disagreed.

"They always learn," he says. "You punish one and educate a hundred. Adolf Hitler. Perfect."

Luca Lozzi/Getty Images

In the shadow of an unfinished cathedral

It's cold and raining on the Verona train platform, on the last day of my journey. I am returning to Tuscany for the moment of truth: Will the Siena crowd abuse Balotelli? Will he leave the field?I meet Fred Marconi outside the stadium.

The AC Milan bus rolls slowly toward the gate, working its way through a mass of fans who've made the trip south. Siena has been assured relegation to Serie B, but Milan needs a win tonight. A tie or a loss will send Siena's hated Fiorentina to the Champions League. When the game begins, some Siena fans cheer for AC Milan, wanting to end Fiorentina's chance at the Champions League. Which is stronger? Hate or love?

"I have really mixed feelings," Marconi says.

Something amazing happens as the game unfolds.

Siena plays like hometown warriors. The mood changes, and the fans go from hoping their team loses to cheering their boys. Siena pushes the tempo, playing rough and hard, and the keeper stops a rocket by Balotelli. Twenty-five minutes into the game, Siena midfielder Alessandro Rosina crosses the ball into the Milan zone. Claudio Terzi heads it into the goal.

Siena is winning 1-0.

Marconi leaps up from his seat, screaming, fists pumping, and the lead miraculously holds, through the end of the first half, into the second. The Siena players hustle, going after every close ball, and Milan spends a lot of time complaining to the officials. Balotelli hits the ground any time an opponent is close to him, and the home crowd whistles and boos when he touches the ball. This crowd leans down into the pitch, the hate of Balotelli palpable, but nobody insults his race.

"They won't," Marconi says, proud.

Milan presses, sending taller, faster strikers down the field, and Siena does its best to cover up, like someone fighting a long-armed boxer.

"We are here! We are here!" the Milan fans scream.

"Your mom is a whore!" the Siena crowd replies, which rhymes in Italian.

The lead holds past the 80th minute, and the fans start to believe, as Balotelli works down toward the goal, getting bumped a bit, hitting the ground like he's been doing all day. This time, the referee gives him the penalty kick. The Siena coach goes crazy, gets ejected. Marconi grips the railing, his muscles tense. Balotelli scores. Milan scores again three minutes later, and the game is over.

Siena has lost another battle.

Marconi almost gets in a fight with a Milan fan who was jumping up and down. They are nose-to-nose, yelling in Italian. Marconi and I disappear into the belly of the stadium, which smells like wet carpet and cigarette smoke. The Siena players look stunned, saying that they thought the game was fixed, and that the system needed them to lose. Outside, Marconi lingers on the hill to look down at the green pitch and the bright flood lights, wondering if they'll be turned on again anytime soon.

The long trip home

Outside the Siena stadium, Balotelli steps onto the AC Milan bus, which has a slick black paint job with red rearview mirrors. The team drives out of the ancient city, already looking toward tomorrow. Football highlights play on a television on the right side, near the front. Balotelli sits in the black-and-red leather seats and exhales, already thinking about reporting to the national team in a few days. The players celebrate the spot in the Champions League, and the end of this long season in the spotlight. Balotelli takes photos with his teammates. In each of them, he grins.The joy in the back of the bus contrasts with stress in the front. Team officials had called the Florence police before leaving Siena, concerned about the reception they might receive when they exited the bus and boarded the train to Milan. They're worried. Balotelli is a target. At the Roma game tonight, the fans abused him when they showed his name on the video board, and he wasn't even there. Then the ultras chanted oo -- oo -- oo oo at a drinks vendor, giving themselves a round of applause when they finished.

Italy is in crisis. I think that's safe to say. Something new is arising out of something old. I don't know whether it's a first breath or a last gasp. James Walston, the professor, thinks all the racial abuse is a sign that Italy has changed, and this is a defiant last stand before a multi-cultural society emerges. Maybe he's right. I don't know.

The AC Milan bus pulls close to Campo di Marte station, and the mood inside changes. Through the dark windows, the team and the officials see a crowd gathered, with the police units there to keep law and order. The air brakes whoosh and squeak. The bus doors open, and the hate-filled voices flood in.

Balotelli steps outside, guarded by police, as a group of 30 Fiorentina fans call him a thief and a cheater. The players rush into the tunnel leading to the train. The racist abuse begins, and Balotelli confronts the abusers, with police and team security officials stepping in between and pulling him away. The team boards its private high-speed train, racing toward Milan. He tweets in English and Italian about leaving the pitch the next time he hears someone attack the color of his skin. They arrive to an empty station, the players and staff taking their gear and heading out into the night.

Milano Centrale is eerie when it's dark and quiet. The players shuffle past the enormous posters of Beyonce. It is approaching 3 when they get outside. A few fans ask for autographs. Some players take the bus back to the facility, but Balotelli leaves in a car. In a week, he will report to national team practice, to represent a country that can't decide whether it wants him to call it home.

The ghost

This story is about a hidden office.A nervous, mousy woman types in an alarm code. She grabs a set of keys, one labeled "balcone." This palace is a museum, dedicated to the treasures of Rome, but not so long ago, it served a different purpose. There's not a single mention anywhere of the man who took the stairs up to the second floor. We are retracing his steps. The public is allowed in one day a week, by request. The nervous woman leads me into a dark hall. She opens a door marked with an exit sign.

We step into an empty room.

She switches on the lights. It's the size of a gymnasium. There is a fireplace at the end, and a glittering chandelier hanging from the ceiling, old crests frescoed on the walls. At the other end, where visitors once entered, the room is sealed with two sets of heavy wooden doors, a narrow space in between, like M's office from the James Bond movies.

The famous balcony is in the far left corner, 26 steps from the door. There's a gold padlock on it. No one is allowed to step outside. They're worried it might become a shrine. The glass on the tall iron-framed door is cracked, and the balcony itself is small, two or so steps deep. A tall man could touch both sides if he stretched out his arms. The Colosseum rises to the right, at the end of the street, and in the middle distance huddle the ruins of the Forum. A church bell rings, and the sound echoes off the tall ceilings. The space will remain empty, under lock and key, until the building falls down or Mussolini's old office is needed again.

Wright Thompson is a senior writer for ESPN.com and ESPN The Magazine. He can be reached at wrightespn@gmail.com.

0 comments:

Post a Comment