Lushai (a Mizo tribe) chiefs at Kolkata during a meeting called by the British. The photo is from 1872, soon after the first military expedition into what is now Mizoram, following violent conflict over land rights.

By Adam Halliday

Looking at century-old images normally throws up some surprises, but

this one was extraordinary.

Joy L K Pachuau points to a photograph, dated 1872, of an open-fronted hut with wooden pillars in the foreground and adorned with articles of ritualistic sacrifices. “There is some mention of it in stories, that it used to stand on the outskirts of villages but we never knew how it looked exactly,” she says.

Pachuau is a Mizo woman who teaches at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University. But her work with the University of Amsterdam’s Professor Willem van Schendel in collecting more than 20,000 photographs to reconstruct the history of the Mizo community and its neighbours has taught her a thing or two about her own culture.

The duo’s ethnological photo exhibition of a few score images, titled “The Camera as Witness: Capturing Mizo Pasts”, and a book with several hundred more images is a pioneering effort. Pachuau and Schendel travelled for years throughout Mizoram, Manipur and Tripura and dug into the archives of UK’s higher learning institutions for these images.

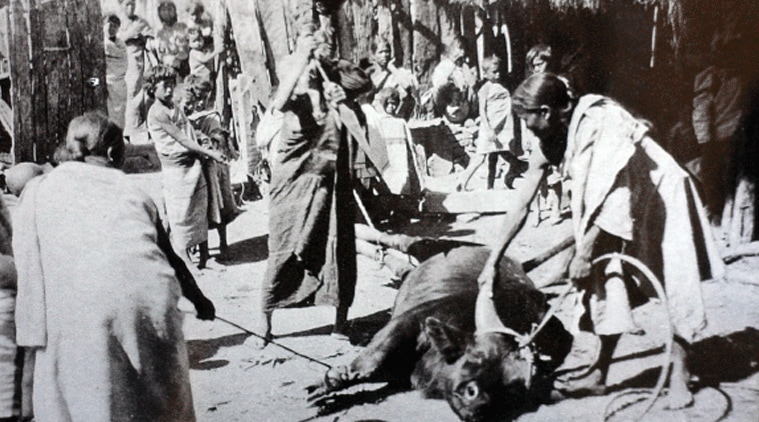

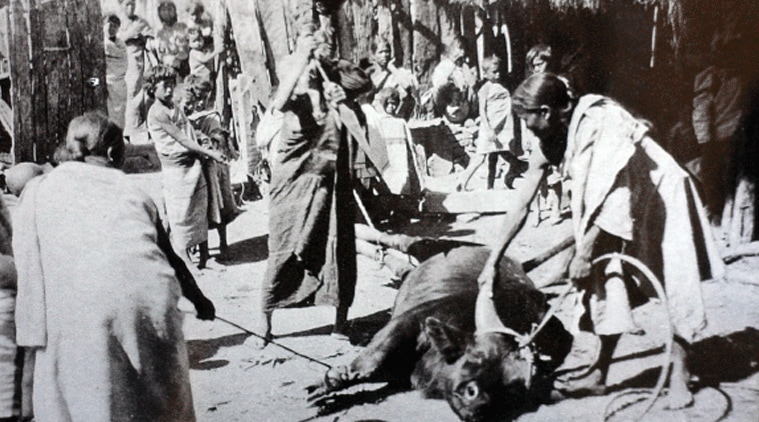

This undated photo shows a ceremonial slaying of a gayal. Such photos of traditional Mizo rituals are extremely rare

Unlike some other large tribal groupings in the Northeast such as the Nagas or even the tribes of Arunachal Pradesh, whose material culture and ways of life were extensively documented by anthropologists and keen administrators, Mizos had few such visitors in their midst. “When we think of the old days, it is an imaginary world. There is nothing visual about how we know our past,” says Pachuau.

Schendel points out another aspect. “Joy and I thought that collecting photos was a way of collecting histories. Writing came very late and it was very little at the start,” he says, referring to the fast-receding oral tradition of the Mizos and the creation of the written word by Christian missionaries at the turn of the 20th century.

It is also unfortunate that whatever images did exist, mostly taken by early Mizo photographers, were lost in the fires that erupted when the Indian Air Force bombed Aizawl’s upper-class neighbourhoods in March 1966. “A lot of the early photos were burned during the troubles,” laments Pachuau, referring the 20-year-period when Mizo separatists fought a guerrilla war with the army.

The oldest images they found date to the 1860s and were the handiwork of early colonial officers, who landed in what is now Mizoram to subjugate the fierce, head-hunting tribes-people, who challenged, often violently, British claims and attempts to convert their traditionally hunting grounds into tea gardens.

These images are an authentic record of the life of Mizos before and around the time prolonged contact was made with communities beyond the dense forests that covered the hills. These include early portraits of Mizo chiefs, warriors and women, memorial shrines and even the process of weaving. One German explorer, Emil Riebeck, who visited briefly, also photographed starving tribesmen gathered at a colonial outpost waiting for handouts during a famine that returns to the hills every 50-odd years.

Later images, mostly taken by Welsh missionaries, show the early changes in baptism methods and church gatherings as well as the first students, some venturing to Silchar and Shillong for higher education. Then came the cowboys — young Mizo men in hats strumming hollow guitars and striking poses reminiscent of James Dean and heroes of grainy-reel westerns. Joy and sadness intermingle even in this section — images of a wedding at a rebel camp, and of a rebel soldier with crates containing the remains of fallen comrades being brought home once peace was declared.

Interspersed in between are images from Myanmar; studio portraits of young musicians who crossed the border to record their songs in a land with better facilities, and bands who came the opposite direction to perform for people who shared common ancestry but who were separated by the realpolitik of borders.

There are plans to take the exhibition to several metros and other Northeastern capitals but schedules have not been fixed yet.

Joy L K Pachuau points to a photograph, dated 1872, of an open-fronted hut with wooden pillars in the foreground and adorned with articles of ritualistic sacrifices. “There is some mention of it in stories, that it used to stand on the outskirts of villages but we never knew how it looked exactly,” she says.

Pachuau is a Mizo woman who teaches at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University. But her work with the University of Amsterdam’s Professor Willem van Schendel in collecting more than 20,000 photographs to reconstruct the history of the Mizo community and its neighbours has taught her a thing or two about her own culture.

The duo’s ethnological photo exhibition of a few score images, titled “The Camera as Witness: Capturing Mizo Pasts”, and a book with several hundred more images is a pioneering effort. Pachuau and Schendel travelled for years throughout Mizoram, Manipur and Tripura and dug into the archives of UK’s higher learning institutions for these images.

This undated photo shows a ceremonial slaying of a gayal. Such photos of traditional Mizo rituals are extremely rare

Unlike some other large tribal groupings in the Northeast such as the Nagas or even the tribes of Arunachal Pradesh, whose material culture and ways of life were extensively documented by anthropologists and keen administrators, Mizos had few such visitors in their midst. “When we think of the old days, it is an imaginary world. There is nothing visual about how we know our past,” says Pachuau.

Schendel points out another aspect. “Joy and I thought that collecting photos was a way of collecting histories. Writing came very late and it was very little at the start,” he says, referring to the fast-receding oral tradition of the Mizos and the creation of the written word by Christian missionaries at the turn of the 20th century.

It is also unfortunate that whatever images did exist, mostly taken by early Mizo photographers, were lost in the fires that erupted when the Indian Air Force bombed Aizawl’s upper-class neighbourhoods in March 1966. “A lot of the early photos were burned during the troubles,” laments Pachuau, referring the 20-year-period when Mizo separatists fought a guerrilla war with the army.

The oldest images they found date to the 1860s and were the handiwork of early colonial officers, who landed in what is now Mizoram to subjugate the fierce, head-hunting tribes-people, who challenged, often violently, British claims and attempts to convert their traditionally hunting grounds into tea gardens.

These images are an authentic record of the life of Mizos before and around the time prolonged contact was made with communities beyond the dense forests that covered the hills. These include early portraits of Mizo chiefs, warriors and women, memorial shrines and even the process of weaving. One German explorer, Emil Riebeck, who visited briefly, also photographed starving tribesmen gathered at a colonial outpost waiting for handouts during a famine that returns to the hills every 50-odd years.

Later images, mostly taken by Welsh missionaries, show the early changes in baptism methods and church gatherings as well as the first students, some venturing to Silchar and Shillong for higher education. Then came the cowboys — young Mizo men in hats strumming hollow guitars and striking poses reminiscent of James Dean and heroes of grainy-reel westerns. Joy and sadness intermingle even in this section — images of a wedding at a rebel camp, and of a rebel soldier with crates containing the remains of fallen comrades being brought home once peace was declared.

Interspersed in between are images from Myanmar; studio portraits of young musicians who crossed the border to record their songs in a land with better facilities, and bands who came the opposite direction to perform for people who shared common ancestry but who were separated by the realpolitik of borders.

There are plans to take the exhibition to several metros and other Northeastern capitals but schedules have not been fixed yet.

2 comments:

This article is really good for all newbie here.

email address lookup tips

I read this article, it is really informative one. Your way of writing and making things clear is very impressive. Thanking you for such an informative article. Hunter Email

Post a Comment