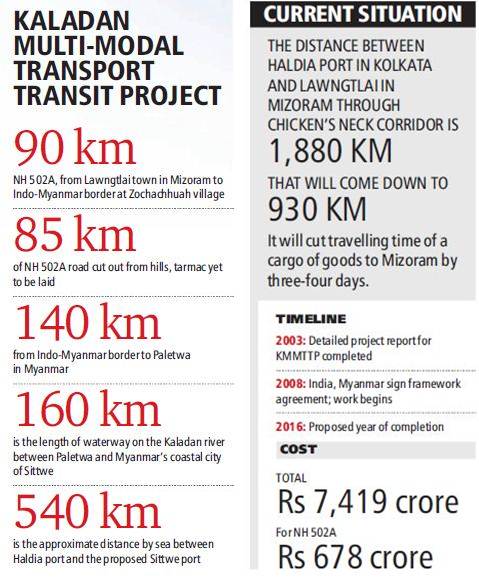

The distance will come down by 930km to be precise.

The distance will come down by 930km to be precise.By Adam Halliday

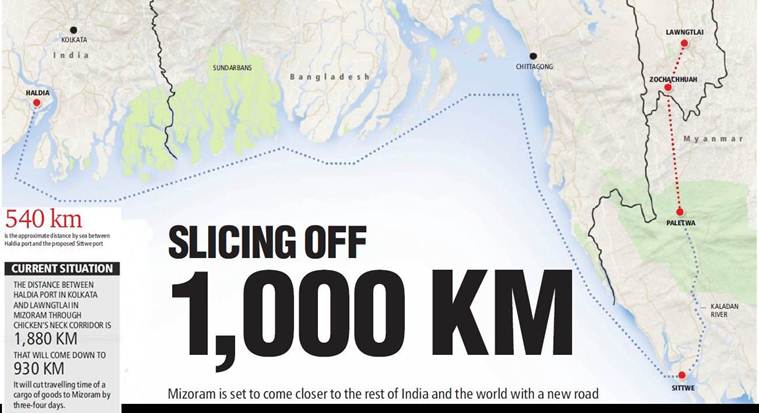

Mizoram is set to come closer to the rest of India and

the world with a new road linking it to Myanmar, and onward to Kolkata.

But first, the project has to take on challenges posed by nature, people

and bureaucracy. Adam Halliday reports.

The road is layered with fresh mud from last night’s downpour. An earthmover has removed the small landslip that blocked it, paving the way for construction to continue, but machines trying to lay the tarmac are struggling against the mud. A steadily growing line of vehicles waits to cross the muddied patch. A worker, overseeing the construction, frantically waves at the vans and cars, trying to clear the track.

Passengers have their eyes set on a steep cliff, apparently worried it might crumble any moment and deposit more mud on the road.

It’s a grind that the construction workers and engineers go through every day, for five years, building a 12-metre-wide, 90-km road from Lawngtlai in southern Mizoram to Zochachhuah village on the Indo-Mynanmar border, running parallel to the Kaladan river. They are now in the process of cutting out the final 5 km of road from the hills.

By the time the final touches, including laying the tarmac, on the road to be called NH 502A are over, it will be mid-2016, two years beyond schedule. But it will shorten the current time taken to transport goods from Kolkata to Mizoram by three-four days, and the distance by more than 950 km. It will also change the face of Mizoram which, like other north-eastern states, is poorly connected to the rest of the country. The benefit may extend to the rest of the Northeast as well, as NH 502A joins NH 54 to Assam.

With eight-odd bridges, NH 502A will be like no other road in Mizoram. As it moves from Mizoram’s hills to Myanmar’s relatively plain topography, it becomes more levelled, wider and straighter than any other road in the state and with gradual rather than steep curves.

Curves. That’s what’s uppermost on Lalthanzuala Ralte’s mind. “I keep browsing the Internet for the length of the longest container trucks and then, when I’m on site, try to imagine if they will be able to negotiate the curves comfortably,” says the PWD Executive Engineer, making a wide, winding gesture from his vantage point at Circuit House in Lawngtlai.

Photos: Adam Halliday

The number of curves on the road are down from the original planned

1,081 to 764, although that’s still more than eight twists and turns

every kilometre.

Photos: Adam Halliday

The number of curves on the road are down from the original planned

1,081 to 764, although that’s still more than eight twists and turns

every kilometre.

NH 502A is part of the much larger, grander Kaladan Multi-Modal Transport Transit Project (KMMTTP). Launched in 2009 by the UPA as part of its ‘Look East’ policy and now being pushed under the NDA’s ‘Act East’ programme, the overall KMMTTP project entails precisely the following: building the 90-km NH 502A to the Indo-Myanmar border; constructing a 140-km highway from there to Paletwa town in Myanmar; developing a river port at Paletwa on the Kaladan river, and connecting it via a 160-km waterway to Sittwe; and constructing a deepwater port at Sittwe to facilitate a sea route to Kolkata’s Haldia port, roughly 540 km away.

Though the Kaladan river runs through Mizoram as well, it is too narrow within the state for barges to travel.

A total of 30 bridges will be built over the total 230 km of road route.

The Myanmar end has been progressing slowly. Work on the highway to Paletwa is yet to begin, though building of the waterway to Sittwe and the development of ports at Paletwa and Sittwe is underway.

Officials in Mizoram call the KMMTTP the “future gateway to South East Asia”. During Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Myanmar this week, MEA Joint Secretary Sripriya Ranganathan called the KMMTTP a “totally win-win kind of a project in which we get the access that we seek to ensure to our Northeast, while Myanmar gets an asset which it will be able to use and that will benefit the people of a fairly backward and under-developed state”.

At a camp of RDS Project Limited, one of the two contractors building NH 502A, Joint Managing Director Rahul Garg is poring over a drawing board. Outside the camp are trucks, an assortment of machinery, workmen from Jharkhand and a temporary diesel pump.

Wiping sweat off his forehead, Garg says, “NH 502A’s starting point — the lone fuel station at Lawngtlai — is roughly 800 metres above sea level. Where I am right now is about 350 metres above sea level. That’s a drop of 450 metres in 70-odd km. Zochachhuah, the border village nearly 30 km away, is about 80 metres above sea level. From there, it’s all small hills.”

Geographical challenges apart, there are bureaucratic hurdles too. Ranjan, project manager for ARSS, hopes his workforce of 360 men can begin laying bitumen in a few weeks. He is confident of finishing the 26 km of road allotted to his company by the revised deadline of mid-2016, but for one hiccup: a tribal farmer on the bank of the small Ngengpui stream is refusing to accept the government compensation. Till he does, ARSS will not be able to build a 100-foot-long bridge over the stream. “The bitumen is already stocked, I have my stone crushers and other machinery in place. But I can only wait now,” he says.

The Mizoram PWD, the nodal agency, has asked for more funds and a second revision of project estimates. The difficulty can be gauged from the numbers: A workforce of 1,010 (including 51 cooks and 305 drivers and various machine operators) and 154 heavy machinery (including 33 excavators, 10 earthmovers and nine bulldozers) are permanently stationed at various points on the stretch, while contractors have set up four fuel pumps to power their operations. By the time NH 502A is complete, the PWD estimates 9 million litres of diesel would have been guzzled, 3,100 trees felled, 1,80,000 cubic metres of stones papered over with 60,000 barrels of bitumen, and 18 million cubic metres of soil removed. There have been 19 deaths since the project began — 13 due to malaria, six because of on-site accidents.

Heavy monsoons here also mean that the annual work season is just eight months long. Mir Thakur, a mechanical engineer with RDS, says he sat at home in Chandigarh for four months during this year’s rains.

In Myanmar, the story is the same. At Sittwe, more than 1.2 million cubic metres of soil, pebbles and rocks have to be dredged for the deepwater port, while an estimated 1,09,000 cubic metres of sand and pebbles have to be dredged to make the Kaladan river between Paletwa and Sittwe navigable for barges.

Sometimes the challenges have been big enough to force a change in course. For example, the initial plan was to link Sittwe with Kaletwa, a town north of Paletwa.

Like in Mizoram, power is erratic in Myanmar, mostly three to five hours a day. And the work season is just five months a year due to flooding of the Kaladan during monsoons, when its water level rises by up to 8 metres.

The Indian contractors insist they can do the job even across the border. Garg of RDS talks animatedly of a night he and his colleagues spent at Kaletwa during a reconnaissance some months ago. Unable to find a hotel, they stayed with a family in a bamboo hut. However, he adds ruefully, a joint venture between RDS and POSCO lost the bid to build the ports at Sittwe and Paletwa and the dredging contract to Essar.

“We will be bidding for constructing a part of the road till Paletwa,” Garg says.

Post-KMMTTP, other roads are being considered to upgrade Mizoram’s infrastructure. Last year, Chief Minister Lal Thanhawla laid the foundation stone for a 120-km road from Laki in Mara-tribe-dominated Saiha district, east of Lawngtlai, to Paletwa. Most tribes in Mizoram, including major ones like Lusei, Mara, Lai, Chakma and Bru, have relatives in either Myanmar or Bangladesh.

In the meantime, some families have already started settling around NH 502A. In fact, 60 Bru families from Darnamtlang village have moved down from the surrounding hills to just the level of the road in spite of objections by the PWD, and even started building a school.

Apart from the local tribes, businessmen can hardly hide their excitement. Expecting that one of the goods to move along the route would be narcotics, and fearing attacks from militants, the Home Department is planning to set up more police stations and check-posts along the stretch.

One “illegality” is already under investigation. Residents in Lai Autonomous District (within Lawngtlai district) have been demanding compensation for “private land”. As per an initial report by the Anti-Corruption Bureau, 1,024 of these “landowners” have made compensation claims for a total of 25,940 sq km of private land. That is 4,859 sq km more than the total area of Mizoram.

Lalrinliana Sailo, chairman of a five-member Estimates Committee, says compensation-related issues are partly behind the PWD asking for a revision of finances by more than Rs 100 crore.

The road is layered with fresh mud from last night’s downpour. An earthmover has removed the small landslip that blocked it, paving the way for construction to continue, but machines trying to lay the tarmac are struggling against the mud. A steadily growing line of vehicles waits to cross the muddied patch. A worker, overseeing the construction, frantically waves at the vans and cars, trying to clear the track.

Passengers have their eyes set on a steep cliff, apparently worried it might crumble any moment and deposit more mud on the road.

It’s a grind that the construction workers and engineers go through every day, for five years, building a 12-metre-wide, 90-km road from Lawngtlai in southern Mizoram to Zochachhuah village on the Indo-Mynanmar border, running parallel to the Kaladan river. They are now in the process of cutting out the final 5 km of road from the hills.

By the time the final touches, including laying the tarmac, on the road to be called NH 502A are over, it will be mid-2016, two years beyond schedule. But it will shorten the current time taken to transport goods from Kolkata to Mizoram by three-four days, and the distance by more than 950 km. It will also change the face of Mizoram which, like other north-eastern states, is poorly connected to the rest of the country. The benefit may extend to the rest of the Northeast as well, as NH 502A joins NH 54 to Assam.

With eight-odd bridges, NH 502A will be like no other road in Mizoram. As it moves from Mizoram’s hills to Myanmar’s relatively plain topography, it becomes more levelled, wider and straighter than any other road in the state and with gradual rather than steep curves.

Curves. That’s what’s uppermost on Lalthanzuala Ralte’s mind. “I keep browsing the Internet for the length of the longest container trucks and then, when I’m on site, try to imagine if they will be able to negotiate the curves comfortably,” says the PWD Executive Engineer, making a wide, winding gesture from his vantage point at Circuit House in Lawngtlai.

Photos: Adam Halliday

The number of curves on the road are down from the original planned

1,081 to 764, although that’s still more than eight twists and turns

every kilometre.

Photos: Adam Halliday

The number of curves on the road are down from the original planned

1,081 to 764, although that’s still more than eight twists and turns

every kilometre.NH 502A is part of the much larger, grander Kaladan Multi-Modal Transport Transit Project (KMMTTP). Launched in 2009 by the UPA as part of its ‘Look East’ policy and now being pushed under the NDA’s ‘Act East’ programme, the overall KMMTTP project entails precisely the following: building the 90-km NH 502A to the Indo-Myanmar border; constructing a 140-km highway from there to Paletwa town in Myanmar; developing a river port at Paletwa on the Kaladan river, and connecting it via a 160-km waterway to Sittwe; and constructing a deepwater port at Sittwe to facilitate a sea route to Kolkata’s Haldia port, roughly 540 km away.

Though the Kaladan river runs through Mizoram as well, it is too narrow within the state for barges to travel.

A total of 30 bridges will be built over the total 230 km of road route.

The Myanmar end has been progressing slowly. Work on the highway to Paletwa is yet to begin, though building of the waterway to Sittwe and the development of ports at Paletwa and Sittwe is underway.

Officials in Mizoram call the KMMTTP the “future gateway to South East Asia”. During Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Myanmar this week, MEA Joint Secretary Sripriya Ranganathan called the KMMTTP a “totally win-win kind of a project in which we get the access that we seek to ensure to our Northeast, while Myanmar gets an asset which it will be able to use and that will benefit the people of a fairly backward and under-developed state”.

At a camp of RDS Project Limited, one of the two contractors building NH 502A, Joint Managing Director Rahul Garg is poring over a drawing board. Outside the camp are trucks, an assortment of machinery, workmen from Jharkhand and a temporary diesel pump.

Wiping sweat off his forehead, Garg says, “NH 502A’s starting point — the lone fuel station at Lawngtlai — is roughly 800 metres above sea level. Where I am right now is about 350 metres above sea level. That’s a drop of 450 metres in 70-odd km. Zochachhuah, the border village nearly 30 km away, is about 80 metres above sea level. From there, it’s all small hills.”

Geographical challenges apart, there are bureaucratic hurdles too. Ranjan, project manager for ARSS, hopes his workforce of 360 men can begin laying bitumen in a few weeks. He is confident of finishing the 26 km of road allotted to his company by the revised deadline of mid-2016, but for one hiccup: a tribal farmer on the bank of the small Ngengpui stream is refusing to accept the government compensation. Till he does, ARSS will not be able to build a 100-foot-long bridge over the stream. “The bitumen is already stocked, I have my stone crushers and other machinery in place. But I can only wait now,” he says.

The Mizoram PWD, the nodal agency, has asked for more funds and a second revision of project estimates. The difficulty can be gauged from the numbers: A workforce of 1,010 (including 51 cooks and 305 drivers and various machine operators) and 154 heavy machinery (including 33 excavators, 10 earthmovers and nine bulldozers) are permanently stationed at various points on the stretch, while contractors have set up four fuel pumps to power their operations. By the time NH 502A is complete, the PWD estimates 9 million litres of diesel would have been guzzled, 3,100 trees felled, 1,80,000 cubic metres of stones papered over with 60,000 barrels of bitumen, and 18 million cubic metres of soil removed. There have been 19 deaths since the project began — 13 due to malaria, six because of on-site accidents.

Heavy monsoons here also mean that the annual work season is just eight months long. Mir Thakur, a mechanical engineer with RDS, says he sat at home in Chandigarh for four months during this year’s rains.

In Myanmar, the story is the same. At Sittwe, more than 1.2 million cubic metres of soil, pebbles and rocks have to be dredged for the deepwater port, while an estimated 1,09,000 cubic metres of sand and pebbles have to be dredged to make the Kaladan river between Paletwa and Sittwe navigable for barges.

Sometimes the challenges have been big enough to force a change in course. For example, the initial plan was to link Sittwe with Kaletwa, a town north of Paletwa.

Like in Mizoram, power is erratic in Myanmar, mostly three to five hours a day. And the work season is just five months a year due to flooding of the Kaladan during monsoons, when its water level rises by up to 8 metres.

The Indian contractors insist they can do the job even across the border. Garg of RDS talks animatedly of a night he and his colleagues spent at Kaletwa during a reconnaissance some months ago. Unable to find a hotel, they stayed with a family in a bamboo hut. However, he adds ruefully, a joint venture between RDS and POSCO lost the bid to build the ports at Sittwe and Paletwa and the dredging contract to Essar.

“We will be bidding for constructing a part of the road till Paletwa,” Garg says.

Post-KMMTTP, other roads are being considered to upgrade Mizoram’s infrastructure. Last year, Chief Minister Lal Thanhawla laid the foundation stone for a 120-km road from Laki in Mara-tribe-dominated Saiha district, east of Lawngtlai, to Paletwa. Most tribes in Mizoram, including major ones like Lusei, Mara, Lai, Chakma and Bru, have relatives in either Myanmar or Bangladesh.

In the meantime, some families have already started settling around NH 502A. In fact, 60 Bru families from Darnamtlang village have moved down from the surrounding hills to just the level of the road in spite of objections by the PWD, and even started building a school.

Apart from the local tribes, businessmen can hardly hide their excitement. Expecting that one of the goods to move along the route would be narcotics, and fearing attacks from militants, the Home Department is planning to set up more police stations and check-posts along the stretch.

One “illegality” is already under investigation. Residents in Lai Autonomous District (within Lawngtlai district) have been demanding compensation for “private land”. As per an initial report by the Anti-Corruption Bureau, 1,024 of these “landowners” have made compensation claims for a total of 25,940 sq km of private land. That is 4,859 sq km more than the total area of Mizoram.

Lalrinliana Sailo, chairman of a five-member Estimates Committee, says compensation-related issues are partly behind the PWD asking for a revision of finances by more than Rs 100 crore.

0 comments:

Post a Comment