The

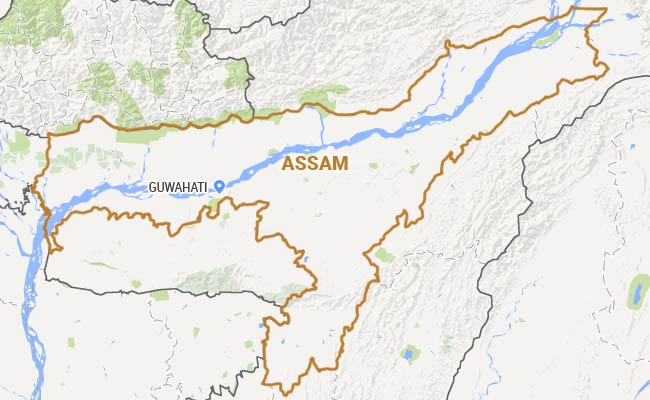

political chessboard this time is arranged very differently from 2016,

and key regions of the diverse state are in unpredictable ferment.Among

the states going into assembly elections in the coming days and weeks,

only one voted for a BJP government the last time around: Assam.The

BJP in Assam is led by chief minister Sarbananda Sonowal and his senior

cabinet colleague Himanta Biswa Sarma,...