What do the stories of a million Indian deaths say about global health? A Toronto researcher aims to find out.

William Daniels/PANOS

On a cool day a few years ago in a village in the northeastern Indian state of Meghalaya, a group of government workers approached a thatched-roof hut. They had learned that a young man in his late 30s had died there several months earlier, and they wanted to ask his family some questions. How did he die? Had he been sick? In India, a medical examination or certificate of death isn’t required before burying or cremating a corpse, and so the workers were conducting a kind of verbal autopsy.

As the young man’s father told them the story—his son had developed a cough, then become sicker until he had trouble breathing—a few children and then a couple of older neighbours gathered around. His son had started smoking at age 10, the man said, but they didn’t know exactly what had killed him, only that he was in the hospital for three days before he died.

The researchers were documenting this story for one of the world’s largest-ever health studies, which is examining one million deaths in India. The study, run out of the Centre for Global Health Research at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, which is partly funded by the Gates Foundation, aims to understand the changing nature of disease in a country undergoing massive societal transformation. It could have huge implications for global health. “By studying the dead, you can understand how to help the living,” said Dr. Prabhat Jha, a professor in public health at the University of Toronto and the founding director of the centre. Already, their model has been so successful it has been adopted by the World Health Organization and is being replicated in studies in places such as China and South Africa.

In India, the 800 field staff trained by Jha and his colleagues visit homes in every part of the country, where they know from census data—which tabulates births and fatalities twice a year—that someone has died recently. Researchers travel primarily by bus to big-city slums, middle-class apartment blocks, wealthy enclaves and the most remote villages to conduct these verbal autopsies. Unannounced, they knock on the door and ask family members to tell the story of how their children, spouses or siblings died.

Not everyone is as welcoming as the man in the hut, particularly in big cities, said Dr. Neeraj Dhingra, a Delhi-based doctor who is collaborating with Jha. “When you knock on the door, they won’t open,” he said. “The wealthy homes are more difficult because they ask more questions.” However, when they learn the research is for a not-for-profit study that may lead to better health services in their community, about 95 per cent participate. Sometimes researchers are invited inside and offered a cup of tea. Sometimes, most often in villages, they sit on a mat on the floor of a hut and pose their questions.

The stories they hear are often heartbreaking, said Dhingra. One case that stands out is that of a five-year-old boy, an only child, who died from enteric fever. His death was preventable, he said, which is true of so many—if only he’d been taken to a hospital. But field staff make no judgment. They record everything that’s said in the local language and never smile or show sorrow. “If someone cries, they say, ‘It is all in God’s hand,’ ” said Dhingra. After the stories are collected, they return to their offices and record the details, and pass the information on to two physicians who determine a cause of death. (A third is on hand in case of disagreement.)

Ten million people die each year in India—that’s over 27,000 people a day. And it is not only the elderly who are succumbing. If you live in India, you have a much higher chance of dying in childhood or in middle age than in Canada. Jha’s study began in 2001 and will continue to collect data until 2014. “In that period, there will be huge changes in India,” said Jha. Already, the country has seen booming urbanization and the growth of a new middle class. When people move to the city, they tend to burn fewer calories. From the 130,000 deaths they have tabulated so far, they have learned heart attacks are the biggest killer, and smoking-related deaths are on the rise, because when people move to the city, they tend to give up traditional beedis (tobacco hand-rolled in temburi leaf) for commercial cigarettes that contain more tobacco. There is also good news: AIDS death rates are four times lower than original estimates by the government and the WHO.

These changes tell the larger story of Indian society. Jha offers his own family history as an example. His grandmother, who passed away last year at 99, witnessed many of the diseases of her era. She remembered the Spanish flu of 1918, and the Bengal famine during the Second World War.

Her father-in-law had succumbed to tuberculosis when her husband was a child. Two of her children died of smallpox. After she moved to the city, one son died of a heart attack and she lost a daughter to diabetes. “What we find is a true snapshot of India at that time,” he said. “I call this a beautiful living lab of what’s happened to health as India has changed.”

Understanding what diseases are killing people in one of the world’s most populous regions is important to every human on earth. “In a globalized world, the main advantage you have is knowledge,” said Jha. “Global health is local health.”

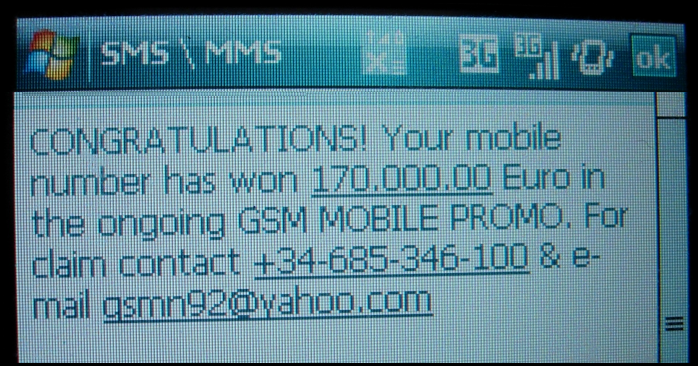

Kohima, Jul 30 : Apart from fraudsters cheating the gullible public of the Northeast through SMS and e-mail making lucrative offer of money, many young people from the region, particularly from Nagaland and Mizoram, are became victims of bank frauds.

Kohima, Jul 30 : Apart from fraudsters cheating the gullible public of the Northeast through SMS and e-mail making lucrative offer of money, many young people from the region, particularly from Nagaland and Mizoram, are became victims of bank frauds.