By Sanjoy Hazarika

In a region like the North-east, where few groups actually

constitute a numerical majority, the State has been involved in unending

and fatiguing efforts to deal with a cycle of demands and

counter-demands

The recent attacks and killings in Assam, Manipur and

Meghalaya by armed non-State groups represent a challenge and test for

the Narendra Modi government and the need to understand the frustrating

complexities of the North-eastern region.

Things are

not being made easy after strident demands by the newly elected

Bharatiya Janata Party MPs from Assam to rid the State of

“Bangladeshis,” a phrase that many from the minority community say is

aimed at targeting them, irrespective of nationality, and one that can

swiftly turn into a security nightmare not just for governments in Delhi

and Dispur, but also for ordinary people caught up in a storm. For a

moment, the “Bangladeshi” issue has moved away from the headlines

because of other events that have captured public attention.

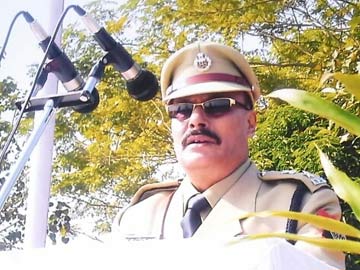

A

Superintendent of Police in Assam’s Karbi Anglong district was shot

dead when his tiny unit was engaged in a fight with an armed group

wanting a separate state for the Karbi community in the jungles of

Assam’s eastern hills — the second major setback that the police in the

State have suffered, an Additional Superintendent having fallen earlier

to the bullets of an armed faction from the Bodo tribe.

Some

400 kilometres west of Karbi Anglong, blurred images emerge of a woman

who was executed gangland style execution after she resisted rape by men

from the “Garo National Liberation Army” in Meghalaya. The GNLA was

launched five years back by a former police officer, who is now in

police custody. But the group is still active, extorting funds, and

carrying out strikes against security forces and civilians.

Rise of insurgent factions

The

law and order situation in the Garo Hills, the home district of

Meghalaya Chief Minister Mukul Sangma, is such that a top official says

that his men could not have moved to the village of the murdered woman

at night as they got word of a possible attack on police convoys. They

got the news when the woman’s family walked into a police station and

told them what had happened. This is a poor reflection of police

capacity, underscoring the need for better equipment as well as strong

political leadership.

These issues underline both

the ethnic and social complexity of the North-eastern region, home to

over 200 ethnic communities, as well as how political mobilisation and

armed violence have changed in these past years. While the principal

militant factions have been sitting at the negotiating table with New

Delhi or in “designated camps” for years, be it the Nagas, Assamese,

Karbis, Bodos and Garos, they are being sharply challenged by smaller,

more violent, breakaway factions.

Armed with new

weapons which are easily available in the illegal small arms markets in

the region, combined with new technology and better connectivity, these

groups are demonstrating the seamless manner in which they can move

across State borders.

The level of violence is

especially stark when contrasted with the extraordinary beauty of the

countryside across all States, although the towns and cities, as

elsewhere, are turning into ugly urban sprawls. The Bodo-Muslim riots in

2012, which displaced nearly half a million people, and the incident

earlier this year when over 30 men, women and children were butchered by

armed men in the Bodo areas are examples of such violence. All the

victims this time were Muslim and the resonance of public anger — of

minority as well as non-Muslim, non-Bodo groups — was visible in the

overwhelming victory of a non-Bodo candidate in a Lok Sabha

constituency.

Amid this fabric, what is often

forgotten is the chain of interconnected events and the contemporary

political narrative: thus, in the Bodo Territorial Council areas, the

first attacks on Muslim and other groups took place in the Bodo areas in

1993. Earlier, few such incidents were reported. There were tensions

over land issues but these had not spiralled into the bloodshed that

followed later.

There is another process that the

Modi government will be aware of — that of manufactured consent. In a

region like the North-east, where few groups actually constitute a

numerical majority — one is not speaking on religious but ethnic grounds

here — the State has been involved in unending and fatiguing efforts to

deal with a cycle of demands, counter-demands, agitations and

resolutions. This has dominated the political discourse in the region.

Thus, almost every State experiencing conflict is witness to a

non-violent process by a group demanding greater powers — such as for a

community or group of communities, putting forth an overall set of

political demands such as greater autonomy or a separate State. Yet,

this runs almost in parallel with violent movements for, ironically,

either similar demands or, going a step further, for “independence.”

This

began with the Naga movement in the 1950s and spread to the Mizo Hills,

Manipur, Assam, Tripura and Meghalaya, although in the latter, armed

movements rose against their own State governments in the 1990s.

In

almost every movement, “outsiders” have been targeted — whether it is

those from another State, of a different linguistic or ethnic group or

the so-called “Bangladeshis.” Yet, today, in almost every State, major

armed organisations which have thrown challenges to Delhi over the past

six decades have abandoned the gun and are either negotiating with the

Centre or engaging in ceasefire. The most visible sign of this was the

landslide victory of a former leader of the United Liberation Front of

Assam from the Bodo areas. He crushed the official Bodo candidate in the

Lok Sabha election and took his oath of allegiance to the Constitution

in Parliament — the very Constitution against which he had taken up arms

earlier.

Yet, agreements and semi-agreements have

been the pattern in the region. These have a history of spawning

breakaway groups which claim to be “anti-talks,” yet want to be at the

table with the big boys; they hit hard at easy targets, showing the

difficulties that police and other forces face in moving through

difficult terrain. The smaller groups too want a share of the funds

flowing into the region and the power that goes with it.

Political

will is critical to dealing with this. Small States like Meghalaya have

been adversely hit by the disinclination of both government and

Opposition leaders in taking a tough line on the “boys” in the Garo

Hills. Earlier Chief Ministers had demonstrated political courage,

authorising crackdowns that forced Khasi and Garo groups to the

negotiating table. It is also not a mere coincidence that the armed

groups concentrate on the coal-rich areas of the Garo Hills where

extraction is highly profitable and where prominent political figures

are said to have business interests.

Thus, a pattern

has emerged over the past decades — New Delhi, to use a BJP catchphrase,

has always tried to appease the largest group agitating or fighting for

a cause or one which is prepared to talk. It has not tried to resolve

the core issue or issues which involve a broader and deeper dialogue

with other groups, and with non-government and civil society figures,

scholars and organisations. Without that kind of work, through mediators

and counsellors, no agreement can work or last.

Perhaps

Delhi thinks it is just a matter of being politically “realistic” — but

such realism has backfired time and again. This was most evident during

the standoff between Telangana and Andhra.

And the North-east, with its

many divergent and parallel ethnic mobilisation processes, is a far

more difficult place. This then is the problem with what one could call

“manufactured comfortable consent” — such agreements rarely last,for

they are designed for short-term gains such as placating a demand,

winning an election, creating a new elite and giving the government some

breathing space. Often, the agitators are not as representative as they

claim to be.

Focus therefore is of the essence, and not haste.

No to rights abuse

The Centre should not be diverted by recent events and instead

concentrate on speeding up the prolonged Naga negotiations (now on for

nearly 18 years). The Delhi-Naga talks do not even have an official

negotiator as former Nagaland Chief Secretary Raghaw Pandey quit before

the election to join the BJP but did not get a nomination. Other

negotiations also need to be pursued with vigour and vision.

The

Modi government must send a clear and unambiguous message to its

members and followers that they cannot take law into their hands over

the issue of “Bangladeshis.” This could spread fear, tension, mistrust

and worse in Assam. Due process must be followed — otherwise there is

acute danger of violence, tragedy and abuse of human rights just because

of a person’s religion. Isn’t the Pune murder of the young Muslim

techie by Hindu thugs a warning and wake-up call? The media must play a

sober role in this because definitions of “Bangladeshis” are often

blurred and arbitrary.

We need to abide by the recent judgment in the

Meghalaya High Court which, while stating the obvious, defined a

Bangladeshi as someone who came to India after the creation of

Bangladesh in 1971. Many tend to look at much earlier cut off dates in

their search for “illegal migrants.”

New Delhi needs

to inform all State governments in the region — whichever the party —

that the murder of innocents, of whichever ethnicity, religion or

language group, and the abuse of rights by armed groups (or security

forces) and local thugs is unacceptable. Such violations need to be met

with a cabrated robust response aimed at showing results in a specific

time frame.

(Sanjoy Hazarika

is director of the Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research at

Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. The views expressed are personal.)

.jpg)